Can a Game Change How We See Nature?

This blog article is based on a presentation I gave at the ISAGA 2024 conference hold in Christchurch, New Zealand, where I was honored to receive the Best Student Paper Award. I’m also happy to share that this work has since been published as a peer-reviewed paper:

Sas, É., Becu, N. (2025). Analyzing Relationship to Nature Within a Game Frame. In: Lukosch, H., Freese, M., Meijer, S. (eds) Simulation and Gaming across Borders. ISAGA 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 15420. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-86555-8_13

Below, you’ll find a recording of my presentation, followed by a written explanation that expands on the main arguments I presented.

My goal is to make this research accessible beyond the academic community — because rethinking our relationship to nature is something we can all engage with.

Have you ever wondered why we think of nature the way we do? Why we often see it as something separate from ourselves — something to be used, preserved, or feared? As a PhD researcher in human geography and design, that’s exactly the kind of question I explore. And surprisingly, I’m using a board game to do it.

Why Reconsider Our Relationship to Nature?

In this research, I focus on a particular aspect of human-nature interactions: not our physical or practical engagements with other living beings, but rather the way we mentally represent nature — and how we position humankind in relation to it. Are we part of nature? Outside of it? Above it?

There are of course many types of relationship with nature, and these differ widely depending on cultural context. For instance, Māori perspectives on nature are profoundly different from those I was raised with as a French woman.

The perspective I am studying — and personally embedded in — is one that is widely shared in many parts of the world today. It is what I refer to as the Classic Modern Western (CMW) relationship to nature*. This particular worldview emerged in Europe around the seventeenth century and has since become dominant in many societies through processes of colonization, then globalization.

Its success and ubiquity have made it almost invisible. So much so that we often forget it is only one way of understanding nature among many possible ones. And yet, it profoundly shapes how we conceive of ecological problems and solutions today. For this reason, CMW worldview can be seen as a conceptual prison* *— a framework so normalized that it limits our capacity to imagine alternative relationships with the living world, which is especially problematic in the context of the Anthropocene.

*Here I draw on Augustin Berque’s concept of the Classic Modern Western (CMW) paradigm.

*Here I use an expression from Descola.

A Research Objective: Deconstructing the CMW Worldview Through Play

One of the core aims of my PhD is to explore how individuals who share the CMW worldview might begin to recognize and deconstruct it. To support this process, I study the potential of simulation games as tools for reflection and critical exploration.

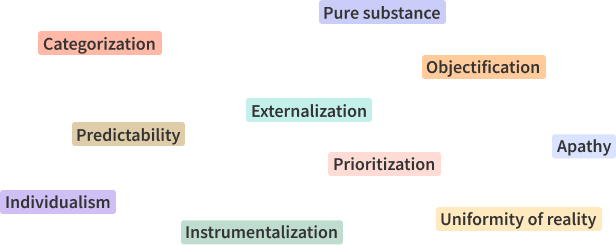

To evaluate this potential, I first developed a conceptual framework to characterize the CMW relationship to nature in more detail. Indeed, this notion was, in itself, too abstract to be directly observed or assessed within a game. This involved conducting a broad (though non-exhaustive) multidisciplinary literature review. I then synthesized the material using four main criteria, such as favoring concepts that appeared across several scientific disciplines.

The resulting framework identifies ten key dimensions that capture the features of the CMW worldview. One example is the dimension of Prioritization, which reflects the tendency to raccord value judgments on other living beings, leading to the sensation of a certain humankind supremacy.

This conceptual framework does not claim to be universal or final; rather, it offers a structured lens through which to observe and interpret how humans express (or question) their relationship to nature.

Applying the Framework to the Game “My Spot of Sea”

I aplly this framework to a specific game: My Spot of Sea. This game was designed before this research, by IFREMER and LIENSs laboratories, in partnership with the association Les Petits Débrouillards. Originally, this game was design to help one understand the functioning of costal socio-ecosystems and also in which way they were linked to human daily activities.

But by superficially observing the reactions of the players, it seemed that this game could also help players understanding their own relationship to nature and that others were possibles.

Based on this, my PhD subject focused on investigating to what extent My Spot of Sea might already foster a critical reflection on the CMW worldview, even though that was not its original design goal.

A Closer Look at My Spot of Sea

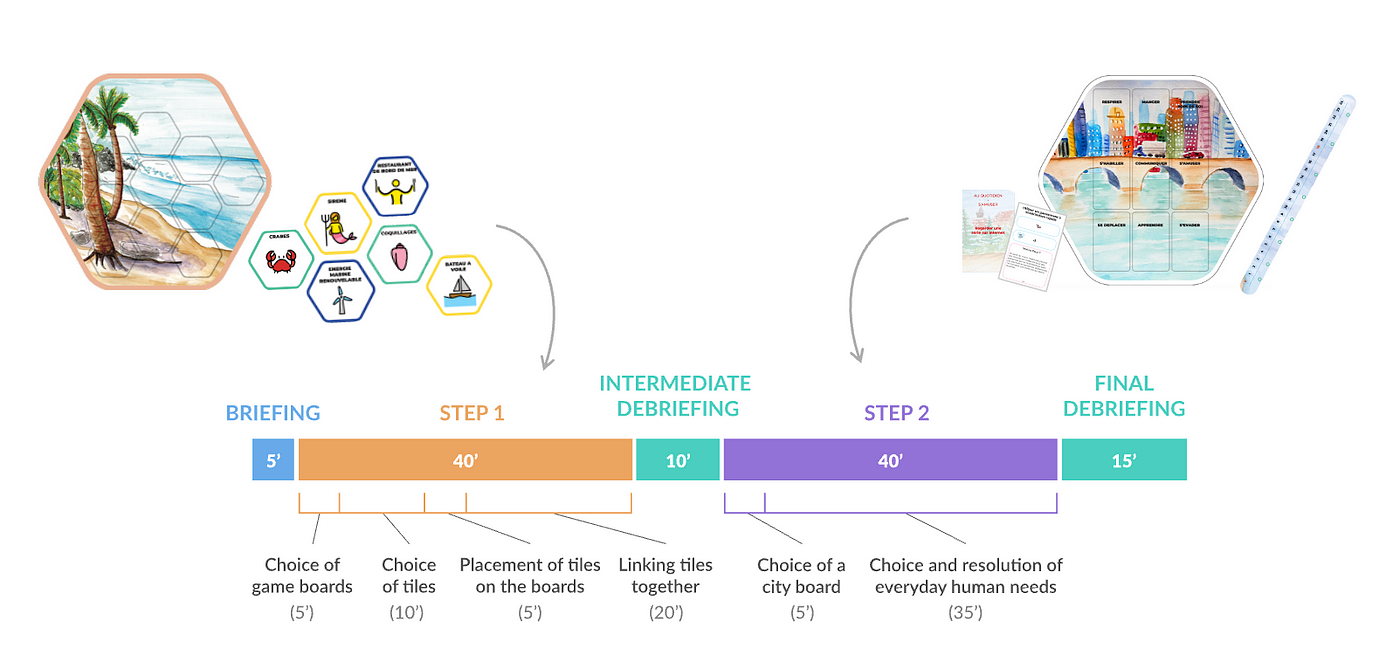

To give a more concrete sense of the game at the heart of this research, My Spot of Sea is a collaborative board game that unfolds in two main steps, each followed by a debriefing.

The first step is like a sandbox where players are invited to build together the best « spot of sea » they all want by putting tiles onto boards. Then, different rules representing the links between tiles are gradually added, and the socio-ecosystem built becomes more and more realistic.

The second step introduces a new layer: the presence of a nearby human city. Players must now meet the human inhabitant’s daily needs, which are drawn from a set of cards. To do so, they are required to reorganize the marine space they previously constructed, solving challenges without reducing the area’s “life points” — a form of ecological health score.

Framing the Research Questions and Hypothesis

By applying our conceptual framework to My Spot of Sea, two main research questions emerged:

- Observability:

Are all the key dimensions of the Classic Modern Western (CMW) relationship to nature — our framework’s components — observable in the gameplay? And if so, how do players express these dimensions during the game?

Moreover, because My Spot of Sea was conceived in a CMW culture without the benefit of hindsight, we hypothesized that the players expressions will reveal very little deconstruction of it.

Indeed, we chose to follow the theory of the non-neutrality of technical artefacts, suggesting that an artifact such as a game reflects the culture of its designers in its design choices, which in turn influence the player. Said otherwise, the relationship to nature of the game designer, if he is not thinking about this biase, will appear through his design choices and then the game designed will influence players to express this same kind of relationship to nature. This way, we hypothesized that some elements of the game (forms, mechanics, animation) would have an impact on the CMW relationship to nature expressed. This leads to our second sub-question:

- Design Influence:

Which aspects of the game influence players’ reflexivity and/or deconstruction of the CMW dimensions?

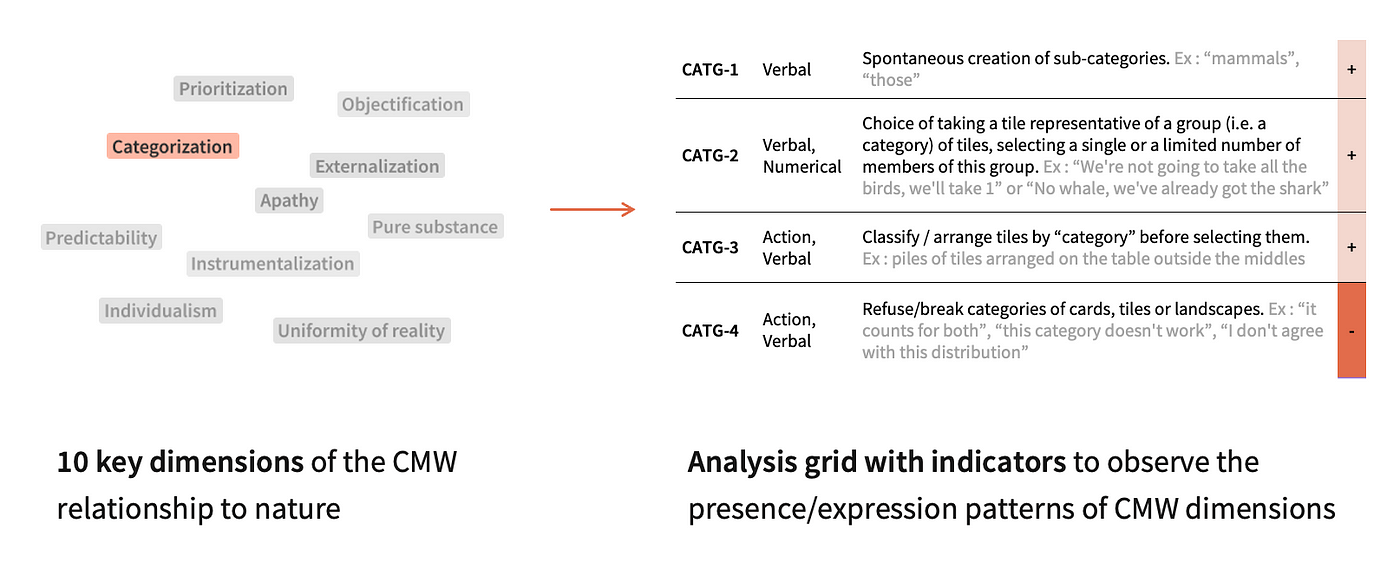

To tackle these questions, we assigned each of the ten dimensions in our framework a set of evaluation indicators.

Method to analyze CMW dimensions with indicators

To make these abstract dimensions observable in gameplay, I translated each of the ten dimensions from the conceptual framework into a set of evaluation indicators. This way, I created an analysis grid including various types of indicators. These indicators allowed us to observe the presence (quantitatively) and expression patterns (qualitatively) of those dimensions in the players and facilitators discussions and game actions during both the play and the debriefing parts

As an example, here is illustrated the part of the analysis grid about the Categorization dimension:

The first three indicators assess the expression of this dimension while the fourth one (in a brighter red) assess when deconstruction of this dimension is express.

Data collection and analysis

To apply this grid, I organized two experimental game sessions in La Rochelle, involving 39 middle-school students, divided into smaller groups. Each group completed a full two-hour game session.

I directly observed these experimental sessions. I also recorded the discussion of each group of players with microphones and the actions performed in the game with cameras oriented towards the table.

After the game sessions, I have made a partial transcription of the discursive material collected while encoded it with indicators. For this, I used the software Sonal to double-encode audio tapes:

- One encoding represents the moments of the game (for example, here the first step of the game is in green and the second in red)

- And in parallel to this, a more precise encoding represents the indicators of the different dimensions of the CMW relationship to nature.

When needed, I also used the video recording and the external observation that I noticed during the session to better understand what happen during the game session, and not only rely on the audio tapes

Results: What Did Players Express?

The analysis generated both quantitative and qualitative insights. Here, I’ll focus on the quantitative side for simplicity.

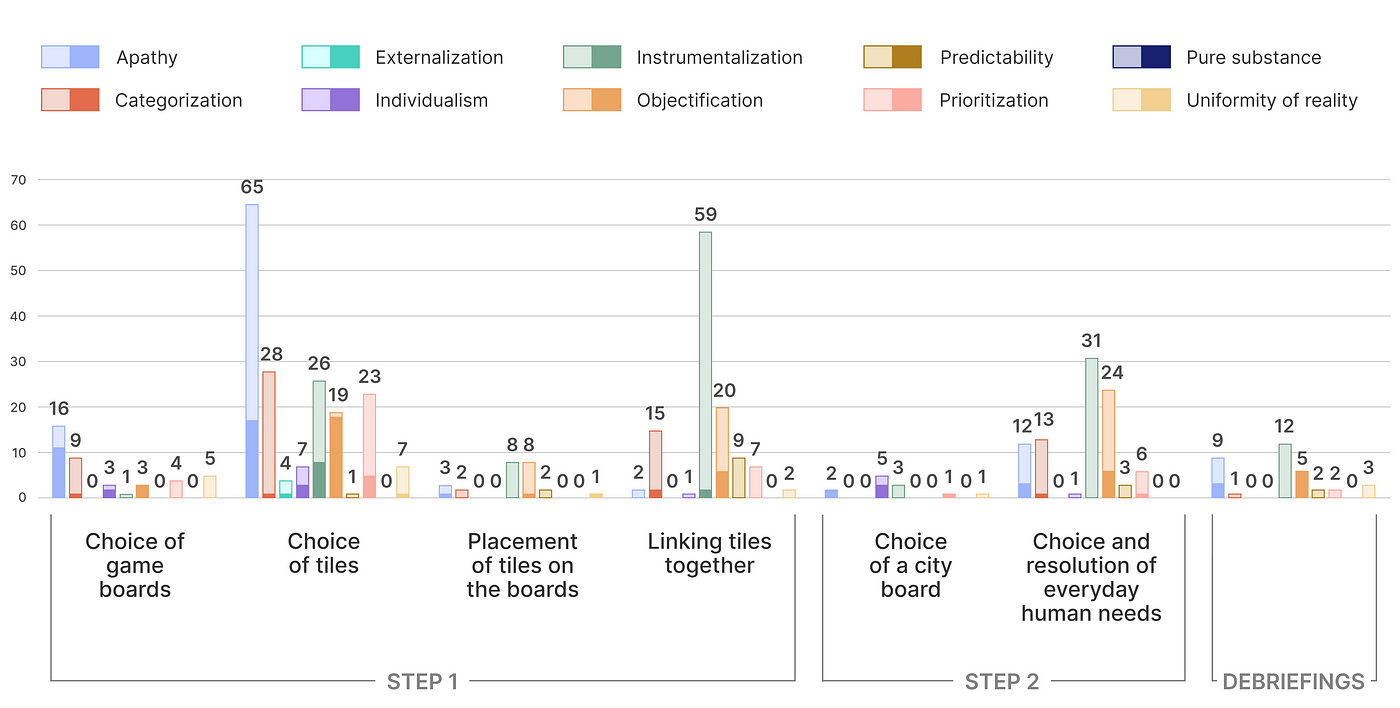

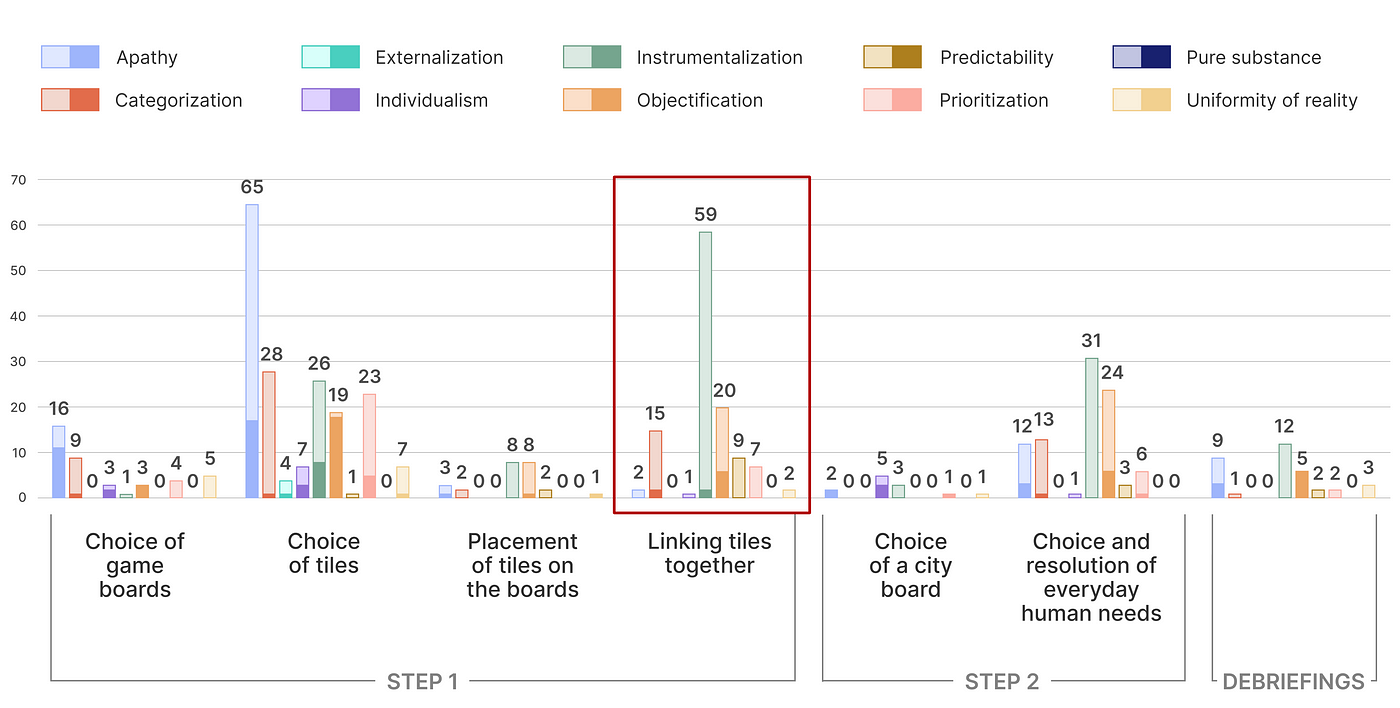

The bar chart below shows how frequently each of the ten CMW dimensions was expressed by players across different phases of the game. In each bar, the full colored filled segment indicates expressions of deconstruction — instances where players reflected on or challenged the CMW logic.

For example, the dimension of Apathy (in light blue)— a kind of emotional distancing from non-human life — was frequently expressed in the first two sub-steps. However, while the initial sandbox phase included a notable number of deconstruction moments (a larg part of the 16 verbatims are in full color), these diminished once the rules became more complex (a much smaller proportion of full color in the 65 bar chart, for example).

Answering the Research Questions

Expression Patterns

Considering our first sub-question, most of the CMW dimensions are indeed observable in the expressions of My Spot of Sea players.

But all the dimensions are not expressed to the same extent: for example, here two dimensions appear with a strong presence. For instance, dimensions like Apathy (illustrated by light blue bars in our chart) and Instrumentalization (in green) were particularly prominent.

Moreover, one dimension, Pure substance (in dark blue), doesn’t appear at all. Thus, we can conclude that all dimensions don’t appear through the game.

Impact of Game Mechanics

Concerning the second sub-question, the results enable to identify some aspects of the game influencing the deconstruction (through reflexivity and/or opposition to) of the dimensions.

The identified aspects correspond mostly to our hypothesis of design effects embed in the game. Indeed, most of the time, the moments of appearance of the pre-identified design effects, correspond here well to the significant expression of the dimension to which they were linked.

For example, the rise of the green bar representing the Instrumentalization dimension coincides with the adding of rules to link tiles together in a context with little space on the boards. Thus, this mechanic seems to nudge players to attribute value judgment on the tiles and to prioritize them depending on their usefulness.

Another example, more general is that the only moments where there is a majority of deconstruction expression within a dimension are the two first sub-steps of the game, corresponding to the freest play moments. It’s almost as if the adding of rules and mechanics nudges players into expressing less deconstruction that they could initially want to express!

Finally, the dimensions are mostly expressed in the first step of the game, as compared to step 2 (even if those two steps have the same duration). It is also interesting to note that during step 1 the students express three times more their relationship to nature than during the debriefing parts (converted to equal time). Thus, based on our results, when it comes to considering our relationship to nature, a free play moment seems to be more effective than a debriefing phase (even though it may appear counterintuitive). This way, these results suggest that the first step of the game is the most relevant for making players express their relationship to nature (even if it’s not necessarily by expressing deconstruction of it).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Taken together, these observations suggest that the current version of My Spot of Sea does not actively encourage players to deconstruct the CMW relationship to nature. In fact, as the game progresses, there is even a decline in expressions that challenge this paradigm. This outcome points to the powerful influence of design effects: the game seems to reflect and reinforce the cultural biases of its designers, rather than prompting critical reflection among players.

However, like all research, this study comes with its limitations:

- The focus was mainly on verbal discourse, without factoring in non-verbal cues such as facial expressions.

- The analysis was confined to the game session, without exploring shifts in players’ perceptions before or after gameplay.

- The conceptual framework and evaluation indicators I developed are open to debate and could be refined.

Looking ahead, I foresee different perspectives for the following of my thesis, such as improving my method. Moreover, I plan to redesign parts of the game, hopping to redirect it towards better expressions of deconstruction. To do so, I will also focus more on design effects, which now appears to me as having more importance that I initially assumed.

Little update: As of May 2025, I’ve already redesigned the game and conducted a new round of experimentation. I’m currently working on analyzing the data — and the first insights are very promising!

Hopefully, I’ll be sharing these new results and developments in an upcoming post, so stay tuned if you’d like to follow how this research evolves.

I hope this way of sharing my research resonated with you!